Range of a projectile

In physics, assuming a flat Earth with a uniform gravity field, a projectile launched with specific initial conditions will have a predictable range. As in Trajectory of a projectile, we will use:

The following applies for ranges which are small compared to the size of the Earth. For longer ranges see sub-orbital spaceflight.

- g: the gravitational acceleration—usually taken to be 9.81 m/s2 (32 f/s2) near the Earth's surface

- θ: the angle at which the projectile is launched

- v: the velocity at which the projectile is launched

- y0: the initial height of the projectile

- d: the total horizontal distance travelled by the projectile

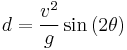

When neglecting air resistance, the range of a projectile will be

If (y0) is taken to be zero, meaning the object is being launched on flat ground, the range of the projectile will then simplify to

Contents |

Ideal projectile motion

Ideal projectile motion assumes that there is no air resistance. This assumption simplifies the math greatly, and is a close approximation of actual projectile motion in cases where the distances travelled are small. Ideal projectile motion is also a good introduction to the topic before adding the complications of air resistance.

Derivations

Flat ground

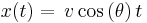

First we examine the case where (y0) is zero. The horizontal position of the projectile is

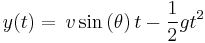

In the vertical direction

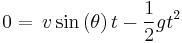

We are interested in the time when the projectile returns to the same height it originated at, thus

By factoring:

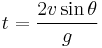

or

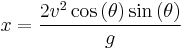

The first solution corresponds to when the projectile is first launched. The second solution is the useful one for determining the range of the projectile. Plugging this value for (t) into the horizontal equation yields

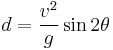

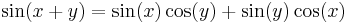

Applying the trigonometric identity

If x and y are same,

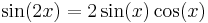

allows us to simplify the solution to

Note that when (θ) is 45°, the solution becomes

Uneven ground

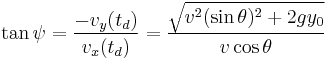

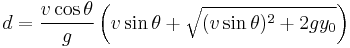

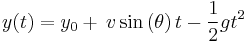

Now we will allow (y0) to be nonzero. Our equations of motion are now

and

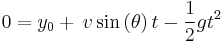

Once again we solve for (t) in the case where the (y) position of the projectile is at zero (since this is how we defined our starting height to begin with)

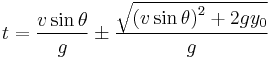

Again by applying the quadratic formula we find two solutions for the time. After several steps of algebraic manipulation

The square root must be a positive number, and since the velocity and the cosine of the launch angle can also be assumed to be positive, the solution with the greater time will occur when the positive of the plus or minus sign is used. Thus, the solution is

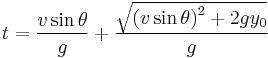

Solving for the range once again

Maximum range

For cases where the projectile lands at the same height from which it is launched, the maximum range is obtained by using a launch angle of 45 degrees. A projectile that is launched with an elevation of 0 degrees will strike the ground immediately (range = 0), though it may then bounce or roll. A projectile that is fired with an elevation of 90 degrees (i.e. straight up) will travel straight up, then straight down, and strike the ground at the point from which it is launched, again yielding a range of 0.

The elevation angle which will provide the maximum range when launching the projectile from a non-zero initial height can be computed by finding the derivative of the range with respect to the elevation angle and setting the derivative to zero to find the extremum:

![\frac { dR } { d\theta} = \frac {v^2} {g} [ \cos \theta ( \cos \theta %2B \frac {\sin \theta \cdot \cos \theta} {\sqrt {(\sin \theta)^2 %2B C} } ) - \sin \theta ( \sin \theta %2B \sqrt { ( \sin \theta )^2 %2B C })]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/dd228045fcdedc1d35152535c906a381.png)

- where

and

and  horizontal range.

horizontal range.

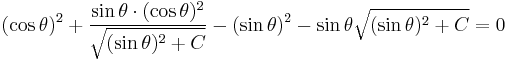

Setting the derivative to zero provides the equation:

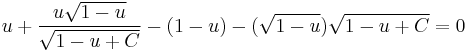

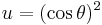

Substituting  and

and  produces:

produces:

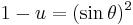

Which reduces to the extremely surprisingly simple expression:

Replacing our substitutions yields the angle that produces the maximum range for uneven ground, ignoring air resistance:

Note that for zero initial height, the elevation angle that produces maximum range is 45 degrees, as expected. For positive initial heights, the elevation angle is below 45 degrees, and for negative initial heights (bounded below by  ), the elevation angle is greater than 45 degrees.

), the elevation angle is greater than 45 degrees.

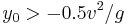

Example: For the values  ,

,  , and

, and  , an elevation angle

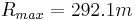

, an elevation angle  = 41.1° produces a maximum range of

= 41.1° produces a maximum range of  .

.

Angle of impact

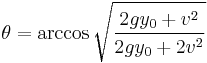

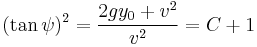

The angle ψ at which the projectile lands is given by:

For maximum range, this results in the following equation:

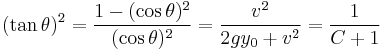

Rewriting the original solution for θ, we get:

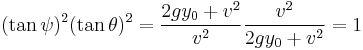

Multiplying with the equation for (tan ψ)^2 gives:

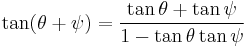

Because of the trigonometric identity

,

,

this means that θ + ψ must be 90 degrees.

Actual projectile motion

In addition to air resistance, which slows a projectile and reduces its range, many other factors also have to be accounted for when actual projectile motion is considered.

Projectile characteristics

Generally speaking, a projectile with greater volume faces greater air resistance, reducing the range of the projectile. This can be modified by the projectile shape: a tall and wide, but short projectile will face greater air resistance than a low and narrow, but long, projectile of the same volume. The surface of the projectile also must be considered: a smooth projectile will face less air resistance than a rough-surfaced one, and irregularities on the surface of a projectile may change its trajectory if they create more drag on one side of the projectile than on the other. Mass also becomes important, as a more massive projectile will have more kinetic energy, and will thus be less affected by air resistance. The distribution of mass within the projectile can also be important, as an unevenly weighted projectile may spin undesirably, causing irregularities in its trajectory due to the magnus effect.

If a projectile is given rotation along its axes of travel, irregularities in the projectile's shape and weight distribution tend to be canceled out. See rifling for a greater explanation.

Firearm barrels

For projectiles that are launched by firearms and artillery, the nature of the gun's barrel is also important. Longer barrels allow more of the propellant's energy to be given to the projectile, yielding greater range. Rifling, while it may not increase the average (arithmetic mean) range of many shots from the same gun, will increase the accuracy and precision of the gun.

![d = \frac {v \cos \theta} {g} \left [ v \sin \theta %2B \sqrt{\left(v \sin \theta \right)^2 %2B 2 g y_0} \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f53a1edde08b3c1c131c0498ea87f8a4.png)